Francis Ladege has been detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) for 28 months. He’s missed three birthdays. He’s missed three Christmases. He is 28 years old and there is no end in sight.

Update 4/6/18: According to Christine Salamone, as of March 30, Francis Ladege has been deported. He is now with his aunt in Juba, South Sudan. As several court decisions are still pending, Ladege’s ability to return to the United States is unknown at this time.

BY: Melissa Wilkinson

Editor-in-Chief

LADEGE MOVED TO the United States from South Sudan as a refugee seeking asylum. He immigrated with his younger brother Charles and other family when he was eight, leaving their mother in a refugee camp. The brothers lived with their grandparents in Louisville for most of their childhood, following them to St. Louis after high school. Ladege received his residency card

in 2003.

He attended Webster University for a semester in 2009 before transferring to STLCC Meramec for several more. It was there he met Christine Salamone, a supplemental instructor who tutored him in physical geography.

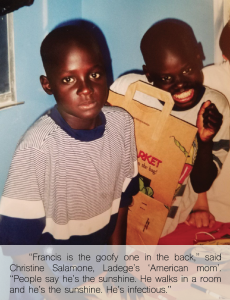

Salamone has two biological sons. Both went to Meramec and studied at UMSL. One is an accountant; the other manages the Wild Birds Unlimited store on Manchester. But when she met Ladege, Salamone quickly gained

a third son.

“I realized that he didn’t have a mom here and that his dad had been killed when he was a toddler…when he was in the military in Sudan. But his mother, I knew she was back home, and that he and his brother would send money back, that he had younger brothers living with the mom,” said Salamone. “I just connected with him. There was something that was just very special. I’ve always been his American mom.”

Though Ladege had dreams of attending Mizzou or studying culinary arts, money kept him from pursuing them. Ultimately, Ladege dropped out of school. Some of his paycheck went to his mother in the refugee camp; some went to his diabetic grandfather. He worked two jobs to make ends meet, eventually earning enough to leave his grandparents’ house and move into an apartment in Crestwood.

Outside of work, Ladege was a typical 21-year-old.

“Francis liked to party. He liked to drink,” said Salamone. “He ended up befriending someone from work…and this friend ended up getting him

in trouble.”

LADEGE’S FIRST RUN-IN with the police was on June 11, 2014, when he was pulled over near his apartment. Crestwood police found marijuana in his car. He was arrested and charged but released when Charles Ladege paid his bond. Later that month he also sold marijuana to covert police officers. In September of the same year, an arrest warrant was issued for Ladege based on the June incidents. He was arrested on Sept. 18 and charged with two counts of selling marijuana and one for intention to distribute.

The Ladege brothers spent their life savings to hire criminal lawyer Richard P. Hereford, who encouraged the elder Ladege to plead guilty to all three counts. He did so on March 5, 2015 and received a five-year

probationary sentence.

If marijuana was his first mistake, this was his second.

If marijuana was his first mistake, this was his second.

“[Hereford] never told him that because you’re not a US citizen, you could be deported,” said Salamone.

Ladege’s probation was going well until October 2015, when he arrived at his probation officer’s office, only to be met with ICE agents who arrested him on-site. They brought him to a detainment facility in Montgomery County, Missouri. “His criminal convictions for a series of aggravated felonies in 2015 on multiple drug offenses rendered him removable,” reads the most recent ICE statement on the matter.

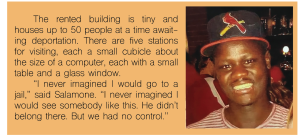

According to Salamone, the rented building is tiny and houses up to 50 people at a time awaiting deportation. There are five stations for visiting, each a small cubicle about the size of a computer, each with a small table and a glass window. Salamone made the drive to Montgomery County every week to see Ladege.

“You can’t touch him. You just put your hand on the window and just have him touch your hand,” said Salamone, holding up her palm. “Or we would hug like this,” she wrapped her arms around her own torso, “and just say you’re hugging each other. I never imagined I would go to a jail. I never imagined I would see somebody like this. He didn’t belong there. But we had no control.”

ICE FLEW LADEGE temporarily to a facility in Pine Prairie, Louisiana in 2016, where he was informed about a warrant for his arrest issued in May 2015, based on his first arrest. Ladege was not aware of the warrant. “On Sept. 20, 2016, a federal immigration judge ordered him removed (deported). On March 9, 2017, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) upheld the judge’s removal order,” reads the official

ICE statement.

In October 2017, ICE flew Ladege back to St. Louis to appear in court, where he pleaded guilty.

“I saw how the system was working then. I saw it first hand,” said Salamone. “They shackle them with their hands and feet and walk them all the way over to the courts and they have to stay that way until the time that they take them back. Sometimes that’s

eight hours.”

He returned to the Montgomery facility after the trial, where he remained until February 2018. That same month, Salamone hired immigration lawyer Michael Sharma-Crawford, who filed two motions to stop Ladege from being deported. The emergency stay of removal was rejected by the BIA later that month, but a decision on the second motion, to reopen and remand Ladege’s case, has not yet been made.

AFTER MOVING AROUND to several ICE detention centers, Ladege is currently in a facility in La Paloma, Texas. There he can watch TV, access the rec room and go outside. But Salamone says Ladege doesn’t feel safe.

She records her calls with him on a tiny battery-powered recorder. It costs Ladege $25 to make a call, money he receives from Salamone. He isn’t allowed much time to talk. Every minute or so, a female voice interrupts the phone line: “In the event that a third party call is detected, your call will be terminated

without warning.”

“There’s a lot of fights going on. We got pepper sprayed,” said Ladege, his voice garbled by the recorder. “A lot of people are so angry and desperate. They just wanna leave.”

But they can’t leave. ICE gives them little information. Many times, Ladege has heard rumors of early morning flights. Each time the flight has been cancelled or rescheduled.

“The flight was supposed to leave in one to three weeks,” he said. “That was three weeks ago.”

According to ICE Public Affairs Officer Shawn Neudauer, detainees are told when, not before, they will be moved.

“No law enforcement agency would announce operational moves prior to beginning them in case someone tried to interfere, which could cause a security situation and place lives at risk,”

said Neudauer.

At this time, Ladege is currently still facing deportation. But according to criminal and immigration lawyer Joseph LaCome, there’s still hope that he could stay. The best case scenario is that Sharma-Crawford’s second motion to reopen and remand Ladege’s case is considered. Another alternative comes in the form of a habeas corpus, which would require ICE to show lawful ground for keeping Ladege detained.

The petition was filed March 12, 2018 by LaCome, who has taken Ladege’s case pro bono.

“Personally, it bothers me. If they really can’t remove him and they’ve just been leading him on…it’s unconstitutional,” said LaCome. “It’s been so long and they still haven’t removed him. The conclusion is they can’t remove him.”

LaCome believes Ladege has yet to be deported because he is “stateless.” South Sudan had not yet received its independence in 1999, when Ladege and his family immigrated to the United States. According to LaCome, South Sudan might not accept him as

a citizen.

Another issue, said Lacome, is that Ladege’s charges were improperly handled. The crime Ladege is convicted of, distribution of under 35 grams of marijuana, is not an aggravated felony, which is the current assumption. This means that Ladege may be able to withdraw his original guilty plea.

“I don’t think [the average ICE officer] would even know that legal distinction. What would have changed if someone knew at the beginning? This is a minor offense, is this worth our resources? Or even if they did charge him he would have had a defense,” said LaCome. “As long as the BIA sees what the legal issue is and then they reverse it, that just resets his whole case. He would go from having this case where he has a final order of removal and they’re treating him like a felon to a simple possession charge. He shouldn’t be under mandatory detention either.”

If Ladege’s guilty plea is withdrawn, said Lacome, it will change everything. The entire basis of Ladege’s deportation is based on his convictions.

“Chances are pretty good,” said LaCome. “Best case scenario is the whole case gets reopened but that

takes time.”

SOUTH SUDAN IS a war-ridden country. Having only gained its independence in 2011, its foundations are still shaky. In 2013, a political power struggle erupted into civil war which still continues today. Hundreds of thousands died and more continue to do so. For most of its people, South Sudan is plagued with famine, mass killings and slave trading. In a November 2017 letter, Ladege called it “a no man’s land.”

Ladege’s aunt still resides there. He’s never met her. She said that food, if you can come by it, is prohibitively expensive. People are thin. Ladege, an average size for an American, would be considered fat.

“He won’t make it here,” she said. “Francis won’t make it here.”

In the meantime, Salamone is collecting resources for Ladege so she can wire him money via western union in the event he is deported. She has a Paypal account going. She has a GoFundMe. She’s organizing bake sales and selling wristbands and t-shirts.

“I’m wearing this color because Francis wears this color every day,” she said, pointing to her bright prison-orange t-shirt. ‘#LetFrancisStay’ is emblazoned on the front, along with details of his situation.

Salamone no longer works for STLCC. Now, she is a full-time advocate for her adopted son.

“I have a new calling,” said Salamone. “I graduated with a human services degree [at Meramec.] I’m doing human services.”

Her next batch of t-shirts will be black and white, because she sees this as a black and white issue. Do something wrong once and you’re

out of here.

“I stand for all those other people waiting,” said Salamone. “When I made the shirts and #LetFrancisStay, it was like, oh my god. Francis isn’t just Francis. Francis stands for thousands and thousands of people. To

let them stay.”

And Salamone isn’t Ladege’s only advocate. Xavier Phillips, president of Meramec’s Student Social Action Committee, is planning a political literacy program to raise awareness of Ladege’s plight and that of others in similar situations. Part of the program will involve a flyer explaining the situation and asking for others to share their personal stories about ICE treatment of friends

and family.

“We can’t ignore this. It’s a very ugly situation that, as Americans and as humans, we have to look in the face,” said Phillips. “I’m trying, SSAC is trying, to raise awareness about it, by simply asking people to look this up. We’re talking about a state-sanctioned version of harassment. You have every right to be angry.”

BUT LADEGE ISN’T ANGRY. His voice, over the tiny static of the recorder, is calm.

“I do believe I was targeted and set up. I don’t know why it happened to me,” he said, speaking to Salamone over the phone. “You guys give me motivation. The friends, the phone calls, all the little things keep me positive

every day.”

For more information on #LetFrancisStay:

https://www.gofundme.com/francis-ladege039s-support

https://www.facebook.com/donotdeporthim