Campus hosts campaign against sex crimes.

By: Taylor Menke

-Staff Writer-

In today’s world of social media and global justice, feminism has taken root through the blogosphere and organizations like Take Back the Night, which began as a slogan at a 1977 antiviolence rally and became an internationally known campaign against sex crimes.

Organizations such as this perpetuate the idea there is no adequate “insurance policy” for rape. Take Back the Night seems to resonate with long-held suspicions by women’s rights advocates about what American society thinks of the word “rape” — that it is committed in dark allies by criminally-minded, unknown men.

In Stacey Lannert’s case, the perpetrator was her father — but she was the one on trial. At the Take Back the Night event hosted on STLCC-Meramec’s campus March 21, Lannert spoke to a crowd of men and women of all ages about childhood sexual abuse and the 1990 murder of her father.

“You’re usually being hurt by someone you love, by someone who is not supposed to do this to you. And when pain comes from that person, you hope that it will never happen again,” Lannert said of the abuse she and her sister endured.

Love for her father kept Lannert reticent about the abuse, mainly because she did not have the vocabulary as a child to tell anyone the truth. By the time that Lannert knew her father’s behavior was wrong, it was too late.

“[I thought], ‘I can’t tell anyone now that he rapes me because I allowed it to happen for so long,’” Lannert said.

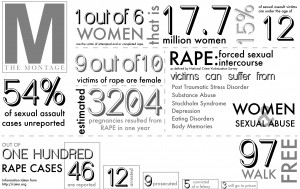

Rape, no matter how it is portrayed in the media, is not commonly committed by strangers. Many reported incidents (approximately 26 perent according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice) occur in the victims’ home; 38 percent of sexual assault crimes are perpetrated by a friend or acquaintance of the victim. Despite the high numbers of assaults per year in the US (over 191,000 in 2005), only 25 perent of these reports result in arrests: the victims sometimes recant, the victims cannot afford rape kits, or the victims decide not to press charges.

From an outsider’s perspective, Lannert appeared to have a decent childhood and a loving family. Behind closed doors, however, her father molested and raped, leading to intense psychological issues and depression in her teens, she said. Shoplifting, nail biting, and promiscuity were Lannert coping methods, and it was only her dream of having children of her own that kept her optimistic.Even these hopes were dashed: her father’s abuse significantly damaged her internal organs, rendering her infertile, lannert said.

Not long after her father began abusing her younger sister, Lannert shot and killed him, thus beginning a long legal battle, which lasted more than 18 years, Lannert said.

“What happened before the crime wasn’t important in the eyes of the law,” Lannert says of her trial in which she was found guilty of first degree murder. “I didn’t qualify for [battered woman’s syndrome] at the time of trial because I wasn’t married to him. The jury was instructed to disregard [the abuse].”

Released after receiving clemency from former Gov. Blunt, Lannert is now an advocate for victims of sexual assault. And she is not alone. Media conglomerates like CNN can no longer create news segments focusing on the “ruined lives” of high school rapists without facing heavy criticism. A backlog of over 20,000 rape kits are being tested. Because of advocacy groups like Take Back the Night, sexual abuse survivors are being given the help they need before they are forced to take desperate measures.

Like other women, Lannert said she dreams of a world where victims are no longer blamed for their abusers’ actions.

“A long time ago, back when this first occurred, it was like, ‘Well, what were you wearing?’ It was always the victim’s fault,” Lannert said. “And it’s never, ever, the victim’s fault. I have a right to walk down the street naked if I so choose — We have a right to be however we want to be, and no matter how we look it should not entice another person to take liberties.”